You can’t talk about the American Revolution without mentioning the involvement of many individuals who also happen to be Freemasons.

In this article, we’re taking a closer look at the state of Freemasonry before, during, and after the American Revolution (1775–1783).

To close it off, we’ll also be highlighting the generals who were also Freemasons and who, ultimately, decided the fate of the (new) USA.

Let’s get started…

Freemasonry Before The American Revolution

The oldest regularly established Masonic lodges in the American colonies of which there is a record are:

- St. John’s of Boston (constituted in 1733)

- Solomon’s in Savannah, GA., and

- Solomon’s in Charleston, S.C. (both constituted in 1735).

There is no reason to believe there were earlier lodges but the record is not altogether clear.

It is certain, lodges were operating in Philadelphia as early as 1730, and there is a tradition that a lodge was working in Boston, authorized by the English Grand Lodge in 1720.

Benjamin Franklin in his newspaper, “The Gazette,” for December 8, 1730, observed that there were several lodges of Freemasons “erected in this Province.”

Documentary evidence of regularity really begins with June 5, 1730, when the Duke of Norfolk, Grand Master of Masons in England, gave a deputation to Daniel Coxe, appointing him Grand Master of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, for a period of two years.

There is grave doubt as to whether Coxe ever exercised his powers and this uncertainty has given rise to much controversy concerning the regularity of lodges established at that time.

There is no doubt of the regularity of the Grand Lodge that came into existence in Boston in the summer of 1733.

In April of that year, the Grand Master of England gave a deputation to Henry Price of Boston, appointing him Grand Master of New England and “the domination and territories there unto being.”

The Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania came into existence and its real history begins when Benjamin Franklin was raised a Master Mason about 1730 or 1731.

In 1734, he brought out an edition of the Constitutions, the first Masonic book to be published on the American continent.

Copies of this book are still in existence and may be seen in the Library of the House of the Temple, in Washington, D.C., in the library in Philadelphia, PA., and in the library at Cedar Rapids, MI.

In the same year, Franklin was made Grand Master and Freemasonry was firmly established.

Thus, we find that Masonic lodges were established in Massachusetts in 1733, in Pennsylvania about 1730, in Georgia in 1734, in South Carolina in 1735, in New Hampshire in 1736, and in New York in 1737.

Another decade saw the spread of Freemasonry to Virginia in 1743 and Rhode Island in 1749 followed in the succeeding years by Maryland and Connecticut in 1750, North Carolina in 1753, New Jersey in 1761, and Delaware in 1765, thus completing the roster of the Colonies long before the outbreak of the Revolution.

During this period, the mother Grand Lodge of England was being disrupted by the controversies that resulted in the trials to separate the Church from a religious body that was to split the Craft and set the brethren into two hostile organizations until the reunion in the early part of the nineteenth century.

This controversy affected American Masonry somewhat and both “Ancient and Modern” lodges were established in the Colonies.

During this same time, lodges were formed in connection with Army units known as “Military Lodges”.

These lodges were destined to play a large part in revolutionary history. How great a part they played we can only assume. Under the circumstances, records were few and uncertain and there was little opportunity to preserve them.

However, we do know that they were important factors in the military activities of the time. At the time of the Revolution, it was estimated there were more than one hundred stationary lodges and fifty Military Lodges in this country.

Freemasonry During The Revolutionary War

When the first Continental Congress met in Philadelphia, nine English Lodges, four “Modern” lodges, five “Ancient” lodges and one Scottish lodge had been warranted in that city.

From the best available records, it is estimated that there were approximately one thousand Masons in that city.

The first men of the city and state were among their number.

The membership of old St. John’s Lodge Number 1 alone, included nine lawyers, of whom seven were judges; four Mayors of Philadelphia, two High Sheriff’s, two physicians, two coroners and two Governors of Pennsylvania.

No less than eight were scientists of great distinction and were members of the American Philosophical Society.

The same was true throughout the colonies; the men of education, culture, prominence, and leadership were members of the Masonic Lodges.

Men like Joseph Warren, (later General Warren lost his life at Bunker Hill,) and Paul Revere in Mass., Ethan Allen of Vermont, Roger Sherman of CT., John Sullivan (later a great Revolutionary General from New Hampshire,) Franklin of Philadelphia, Robert Livingston of New York, George Washington and Patrick Henry of Virginia and many others among the recognized leaders were Freemasons.

When the war was declared, and every citizen had to take his stand, either for or against independence, it was found that every Masonic leader was among the patriots.

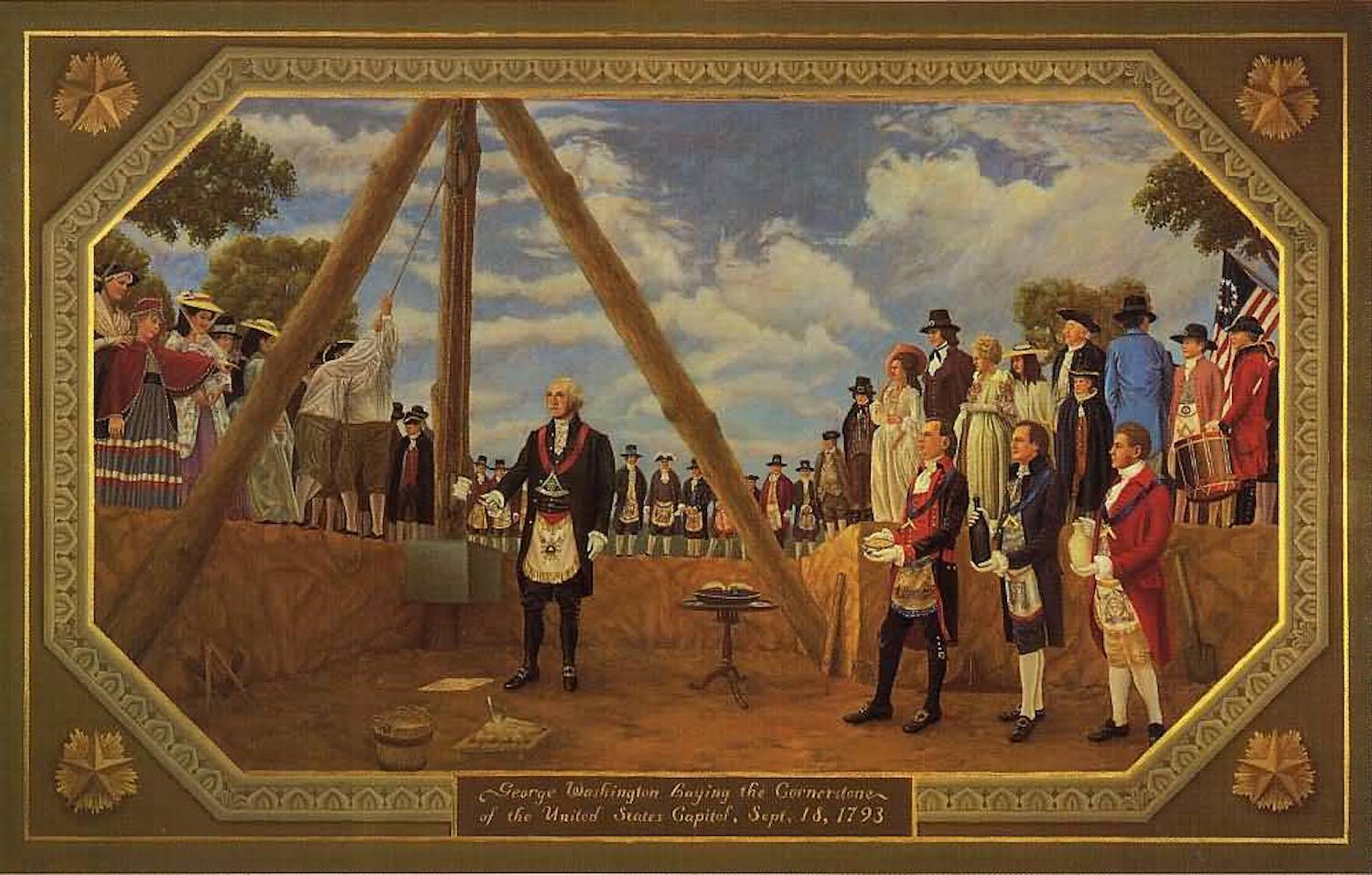

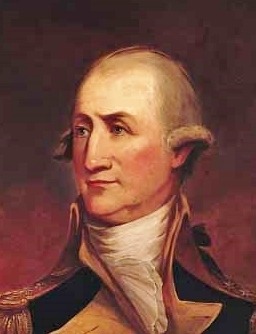

As an illustration of the influence Masonry exerted at that time, was of the appointment of George Washington as Commander-in-Chief of the Revolutionary forces.

It was said Washington was chosen partly because of the fame he had won in the Braddock expedition, and partly to ensure the support of the Southern Colonies.

The men over whom he was placed in command were simple, democratic, hard-working people, dissenters to the backbone.

Washington was a Freemason, and as such, was acceptable to the leading patriots in both civil and military life.

The Military Lodges, to which were referred to earlier, continued to function during the war. Attached to particular regiments they followed the movements of the regiment and flourished under the vicissitudes of the conflict.

Washington and other Masonic Generals visited these lodges from time to time and distinguished foreign Masons, such as Lafayette and von Stueben were frequent visitors.

In fact, there is a story that Lafayette was made a Mason in a Military Lodge in the presence of Washington.

This story, however, is largely discredited, as there seems to be conclusive evidence that Lafayette was raised a Master Mason in a French Lodge before coming to America.

There is greater evidence that Alexander Hamilton was made a Master Mason in a Military Lodge.

These Military Lodges were a source of patriotic enthusiasm, a continual incentive to patriotic “fervour,” and aided materially to the discipline of the Continental Armies and furnished a meeting place for brethren engaged in a great crusade and bound together by the mystic tie of their “Brotherhood” fraternity.

Masonic Leaders in the Revolutionary War

Of the men who signed the Declaration of Independence, the following are known to have been members of the Masonic Fraternity:

William Hooper, Benjamin Franklin, Matthew Thornton, William Whipple, John Hancock, Philip Livingston, Thomas Nelson, and no doubt others, if we had the Masonic records that were destroyed during the war.

Indeed, it has been said that, with four men out of the room, the assembly could have been opened in form as a Masonic Lodge on the Third Degree.

Not only Washington, but also nearly all of his Generals were Masons, such as Greene, Lee, Marion, Sullivan, Rufus and Israel Putman, Edwards, Jackson, Gist, Baron von Steuben, Baron DeKalb and the Marquis de Lafayette.

If the history of these old camp lodges could be written, what a story it would tell.

Not only did they initiate such men as Alexander Hamilton and John Marshall, the immortal Chief Justice, but also they made the spirit of Freemasonry felt in “times that try men’s souls,” a spirit passing through the picket lines, eluding sentinels and softening the horrors of war.

Famous Freemasons During The American Revolution

George Washington & His Generals

Washington, according to Lafayette, never willingly gave the independent command to officers who were not Freemasons.

Nearly all the officers of his official family, as well as most other officers who shared his utmost confidence, were his brethren of the “Mystic Tie.”

Washington and his Masonic Generals encouraged the organization of Military Lodges. They attended, whenever possible, the meetings of the regular lodges in their neighbourhood.

They frequently shared with their Brethren the labours and festivals of the Craft.

Unquestionably, the common teachings and principles fostered the spirit of harmony and Brotherly Love among them and enabled them to meet and work together with mutual confidence to a common end.

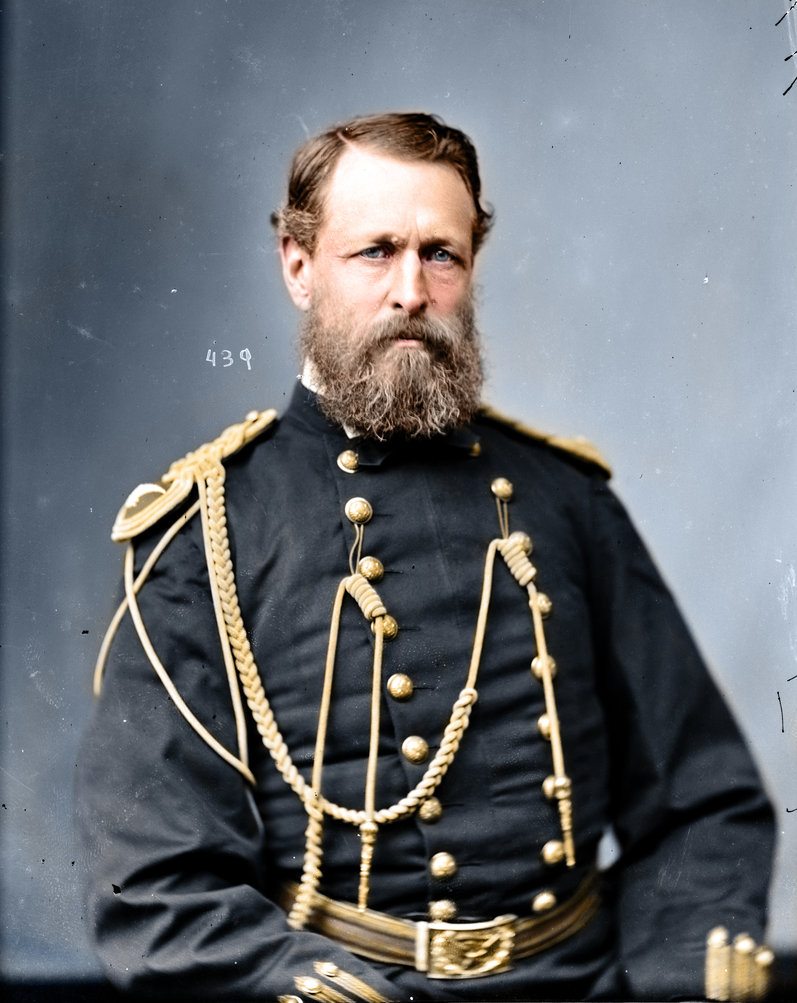

General Warren

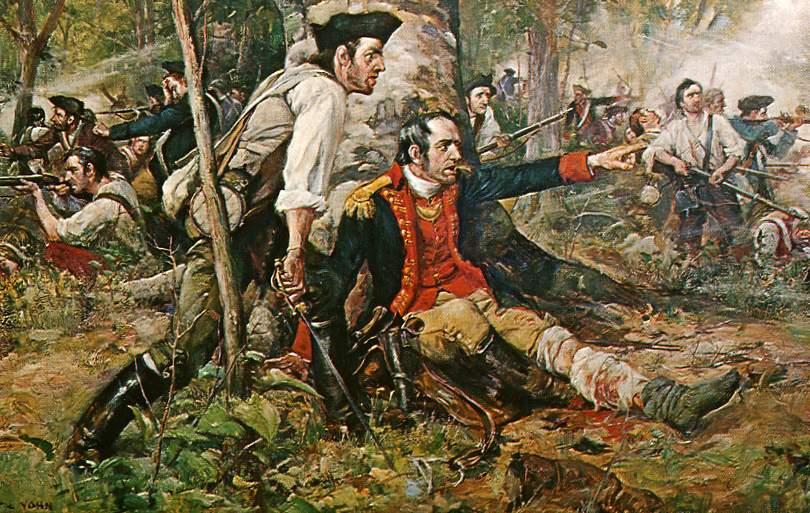

General Joseph Warren was born in 1741. He was killed in the battle of Bunker Hill, 1775.

He was President of Massachusetts Congress in 1774. He was commissioned Major General in 1775. Was initiated in St. Andre’s Lodge in Boston on September 30, 1761; passed November 2.

The exact date of his raising is unknown. He was Master of his lodge in 1769 and in the same year received from the Earl of Dalhousie, Grand Master of Masons in Scotland, a commission dated March 3, 1772, bearing the date of May 30, 1769, appointing him Grand Master of Masons in Boston and within one hundred miles of the same.

Later, he received a Commission dated March 3, 1772, issued by the Earl of Dufries, then Grand Master of Masons in Scotland, extending his jurisdiction over the continent of America. When Elbridge Gerry warned him against unduly exposing himself at Bunker Hill, he exclaimed,

“I know that I may fall, but where is the man who does not think that it is glorious to die for his country?”

John Paul Jones

Founder of the American Navy and was a famous sea fighter.

He was born on July 6, 1747. Admiral John Paul Jones was the first officer commissioned in the American Navy. He was the first to command a war vessel. He was the first to run up the American flag over a war vessel, the Alfred, in 1775.

The first and only naval officer named in the Act of Congress for creating the new flag, the Stars and Stripes.

The first to propose and receive a salute to the Stars and Stripes from a foreign nation, France; first to make a British “man’ o’ war” strike its colors and surrender to the Stars and Stripes, and the first naval officer to receive a note of thanks from Congress.

John Paul Jones received his E. A. Degree in ST. Bernard’s Kilwinning Lodge No. 122, Kirkcudbright, St. Mary’s Island, Scotland on November 17, 1770.

It is reported that he took his F. C. Degree and M. M. Degree in the Royal White Hart Lodge at Halifax, North Carolina

General David Wooster

He was born in 1710. He died in 1777.

He was one of the originators of the attack of Fort Ticonderoga. It was captured, and destroyed, in 1775. He became Master of Hiram Lodge in Connecticut in 1750.

General Nicholas Herkimer

He was born in 1717. He died in 1777. He took part in many battles of the war. He died because of wounds received at Oriskany. Was a member of St. Patrick’s Lodge in New York.

Nathan Hale

Nathan Hale was a Mason before he was twenty-one years old.

General Hugh Mercer

He was born in Scotland 1721. He died from wounds received at Princeton in 1777. He was a brave, resourceful officer.

He was a member of Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4, in Virginia, the lodge in which George Washington was made a Mason.

General William Whipple

Born in 1730. Died in 1785. He was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. He was a member of St. John’s Lodge No. 1, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

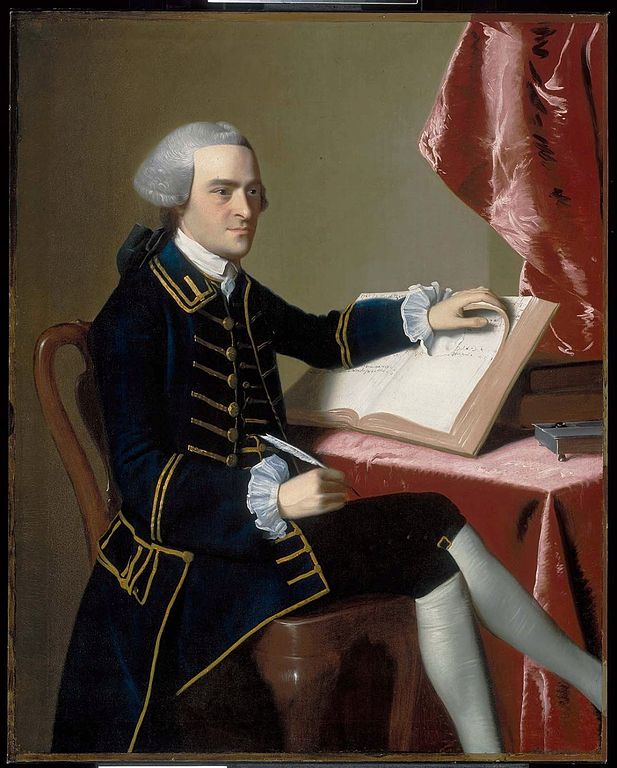

John Hancock

Born 1737. Died 1793. He was the first signer of the Declaration of Independence. On his statue in the Capitol are these words:

“He wrote his name where all nations should behold it and time should not erase it.”

He was President of the Continental Congress from 1775 until 1777. He was the first Governor of MA. He was a member of St. Andrew’s Lodge in Boston and became Grand Master of Masons in MA.

General John P.G Muhlenberg

Born in 1746. Died 1807.

Entered Lutheran Ministry. In early days of Revolution, after impassioned pleas to his parishioners to rebel against Great Britain, suddenly threw aside his clerical robes, stepped forth in the uniform of a Virginia Colonel, and recruited 300 men on the spot. He was with Washington at Brandywine, Monmouth, Stony Point and Yorktown.

He was a Mason but details are unknown.

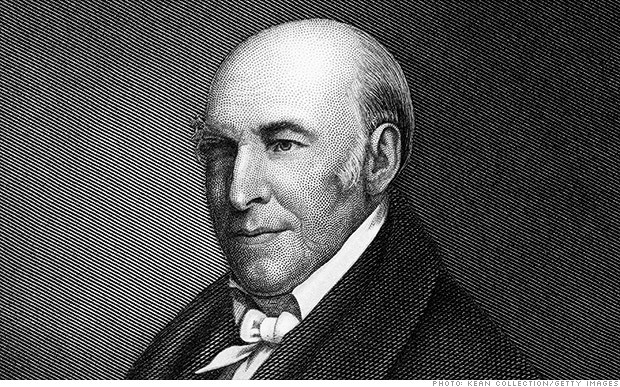

Stephen Girard

Born in France, 1750. Died in 1831. He was a great merchant, great philanthropist and a great Mason.

He had a most romantic career. He was an enthusiastic supporter of the Revolutionary cause.

He was made a Mason in 1788. He held membership in Union Blue Lodge No. 8, in Charleston, S.C.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XW9xomc9htw

FREE DOWNLOAD: 100 FACTS ABOUT FREEMASONRY (ALMOST NOBODY KNOWS)

Join the 10,000+ Brethren from around the world inside our weekly Masonic newsletter and get our best selling ebook for free (usual value: $20).